A5 Math: The Long Version

Here, we'll give you the gory math details behind the "world

according to you" in answer A5. You may wish to read the friendly

explanation under A5 first.

A highly simplified model

In crafting output graph A5, we use a highly simplified model. We assume that if:

P1: AI is possible in principle; and

P2: We have hardware enough to run neuromorphic AI; and

P3: We have enough neuroscience and other knowledge to know how to build neuromorphic AI, then

A5: Neuromorphic AI will be built.

Each

of propositions P1, P2, P3, is assigned a probability based on your

answers to Q1 through Q5. These probabilities are then multiplied

to get the "probability of neuromorphic AI, according to you" in

A5. For example:

Prob(A5:

We have neuromorphic AI in the year 2030) = Prob(P1: AI is possible in

principle) * Prob(P2: We have enough hardware in 2030) * Prob(P3: We

have enough knowledge of how the brain works in 2030).

Again, P1

through P3 get their probabilities from your answers. If you

enter different answers for questions Q1 through Q5, you'll get a

different A5 graph out.

(If this model seems ridiculously

simplistic, don't despair. You'll get to create a less

ridiculously simplistic model of AI in A10, after you answer more

questions.)

How P1 is set

P1 records whether AI is

possible in principle. P1 does not vary by year: we're imagining

that the gods roll dice before history starts, and, unbeknownst to us,

the dice come up saying AI is permanently either possible or

impossible. In Q1, you choose the weighting on the gods' dice:

you input the probability Prob(P1) that AI is possible in principle.

How P3 is set

P3

records whether we have enough neuroscience knowledge to be able to

build neuromorphic (brain-like) AI if given enough hardware. P3 does vary by year: our brain knowledge might be insufficient in 2030, but sufficient in 2040.

So,

for P3, we might imagine the gods roll dice continually while history

runs. At any year from 2010 to the model's end in 2070, the dice can

come up saying, "yes: neuroscience has made enough progress". But some

years are more likely than others, and your inputs determine which

years are more likely.

(Keep in mind that what comes out of our

model isn't one random run of history. It's how the outcomes of all

possible runs are distributed; the math that determines this

distribution isn't itself random.)

More specifically, your input on question Q5 determines a lognormal distribution

on the year we'll have enough neuroscience knowledge. (We imagined the

gods rolling dice continually; but actually, if you believe in

lognormal dice, it's simpler to imagine the gods reading off a year

from one of those at the beginning of time. There's a way to calculate what the dice weightings for rolling continually would need to be.)

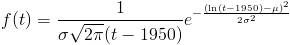

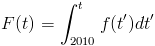

If mu and sigma are the mean and standard deviation (of the logarithm) you choose in Q5, the probability density that P3 will become "sufficient brain knowledge" at time t is

and the cumulative probability that P3 will have become "sufficient brain knowledge" any time before time t is:

(If you want to know why we used a lognormal distribution, read our FAQ entry. 1950 was chosen as the zero point for the lognormal because it was the approximate beginning of serious AI work.)

How P2 is set

P2

records whether the best-funded project has enough hardware so that,

with enough knowledge, it could simulate neuromorphic AI. You chose the

distributions for P1 and P3 for yourself. But P2 depends on three

variables:

V1: The amount of computing power available for a dollar.

V2: The money available to the best-funded project.

V3: The amount of computing power needed for neuromorphic AI.

For

P2 to hold, the amount of computer power the best-funded project can

buy for the money it has available has to be at least equal to the

amount of computing power needed for neuromorphic AI. Taking 2030 as an

example, in math:

Prob(P2: The best-funded project has enough

hardware in 2030) = Prob(V1 (computing power per dollar in 2030) * V2

(dollars available) > V3 (computing power needed)) = Prob(V1 >

V3/V2).

money, hardware

V2 and V3, money available and

computing power needed, are both set at the beginning of time: both are

some unknown number that stays the same throughout the years. Again, we

give these numbers lognormal distributions. You set the parameters by

answering question Q4 and Q3.

You can see V3/V2, computing power needed divided by money available, as an efficiency threshold:

if you can get more hardware for a dollar than this threshold, P2

holds. Dividing a lognormal variable by another amounts to subtracting

a normal variable (the log) from another. And the difference between

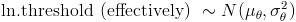

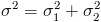

two normal variables is normal with  and

and  . So our efficiency threshold is lognormally distributed with these parameters.

. So our efficiency threshold is lognormally distributed with these parameters.

efficiency

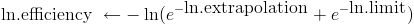

V1,

the other side of the equation, is a little more complicated. In Q2 you

gave a "year when Moore's law stops". But actually the model doesn't

have Moore's law stopping abruptly, with hardware available per dollar

suddenly bumping into ceiling X. Instead, it gradually approaches X as

an asymptote.

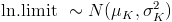

Furthermore, you don't know what X is: the ending

year you gave had a normal distribution around it. As long as Moore's

law continues, hardware per dollar rises exponentially; and so this

normal distribution for the ending year gives you a lognormal

distribution for the long-run limit. Before this limit, the distribution we use is more complicated; see footnote.

Now

that we've turned your answers into probability distributions for the

efficiency (V1) and the efficiency threshold (V3/V2), what remains is

to compare these, outputting a final probability for P2 each year. For

details on how we did this, see footnote.

That's it! We now have probabilities for P1, P2 and P3 each year. The product of these for each year is A5.

footnote: